Boston’s Emancipation Memorial (photo by author)

A new podcast debuted a couple weeks ago called “Uncivil.” It focuses on the divisions in our country that caused the Civil War and that still divide us today. As their website announces, they aim to “ransack the official version of the Civil War, and take on the history you grew up with.” In its first few episodes it has lived up to that claim, dismantling persistent myths about the Civil War era.

The first episode featured a prologue which left a lasting impression on me. In the segment, hosts Jack Hitt and Chenjerai Kumanyika stand in Lincoln Park in Washington D.C. The sounds of a busy city hum in the background as they describe the Freedman’s Memorial (also known as the Emancipation Memorial). The statue depicts Lincoln standing over a kneeling freedman, his hand extended in a sort of blessing, perhaps bidding him to stand. The freedman still wears shackles but his chains have been broken.

The memorial represents an effort to celebrate a great moment in our history but sadly, as they observe, it looks for all the world as though the freedman is stooping to shine Lincoln’s boots. And it perpetuates the myth of Lincoln as the Great Emancipator, single-handedly striking down slavery with a stroke of the pen.[1] The depiction of a crouched, half-naked former slave does not, as Kumanyika states, “give credit or represent the agency of black people in freeing themselves.” He pauses, then says, “I hate this statue.”

As I listened, I recalled a similar sense of revulsion. I have never seen the Washington statue. But I well remember the first time I saw its copy in Boston when I was in high school. I remember being confused and disgusted. We can assume that this is not the reaction that the artist was shooting for. It is a work of art aiming to convey a positive message…and badly misses the mark. This was apparent even at the time of its unveiling.

According to an inscription on the original Washington version, the funds for the memorial were raised entirely by freedmen. Though African-Americans raised the money, they had no say in the monument’s conceptualization.[2] The monument commission, headed by philanthropic and President of the Western Sanitary Commission James Yeatman, selected a design by well-known artist Thomas Ball, a native of Charlestown, Massachusetts.[3] About a dozen of his works adorn Boston—the best known being the equestrian statue of Washington which dominates the Boston Public Garden.

The depiction Ball chose would have been familiar to many at the time. That doesn’t make it a good choice. But it seems clear he was inspired by a famous etching utilized by many abolitionist publications before the war. Featuring a slave in the same posture uttering the words, “Am I not a man and a brother?” the image was designed in 1787 as the seal of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade—a group of British Quakers. The American Antislavery Society drafted a version as their seal in 1837.

Perhaps Ball chose this image of the abolitionist movement to achieve some emotional impact—recognition that this familiar figure now lacked the chains and could stand. While this image may have been designed to appeal to the viewer’s humanity when slavery still existed, after emancipation it should have been cast aside and Ball should have gone in another direction. As art historian Kirk Savage wrote, the statue was, “a failure to imagine emancipation at the most fundamental level, in the language of the human body and its interaction with other bodies.”[4] An alternative design by Harriet Hosmer (sometimes called the first professional female sculptor) would have featured several African American figures, including a black soldier in Union uniform.[5] This idea was rejected as too expensive—and likely too revolutionary.[6]

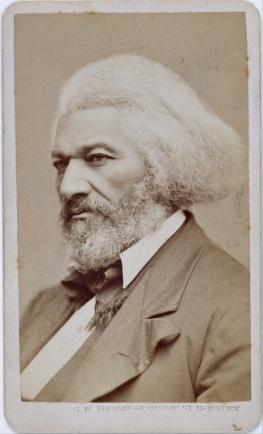

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer, emancipated himself when he escaped slavery in 1838. (Public domain photo courtesy WikiMedia Commons)

So the commission went with Ball’s interpretation. It was unveiled in 1876 and Frederick Douglass gave the dedication remarks. With typical eloquence, Douglass congratulated those who had organized the effort and particularly the freedmen who had funded it—many of whom were present for the ceremony. “We, the colored people,” Douglass said, “newly emancipated and rejoicing in our blood-bought freedom, near the close of the first century in the life of this Republic, have now and here unveiled, set apart, and dedicated a monument of enduring granite and bronze…” in which could be read something of the “exalted character” of Abraham Lincoln.[7]

John W. Cromwell, a young African-American attorney, active in creating educational institutions for freedmen, sat near the podium when Douglass gave his remarks. He later asserted that Douglass, while complimentary of the effort, gave an off-script aside from the podium which was left out of the published transcripts. According to Cromwell, Douglass “was very clear and emphatic that he did not like the attitude; it showed the Negro on his knees, when a mere manly attitude would have been more indicative of freedom.”[8]

A copy of this flawed statue came to Boston in 1879 through the efforts of Moses Kimball, a politician and showman. Kimball was a close associate of P.T. Barnum and ran the Boston Museum—a conglomeration of curiosity exhibits, theater and lecture hall which once stood on Tremont Street. Boston’s Emancipation Memorial is now hemmed in by new buildings but initially occupied a prominent spot in the middle of Park Plaza in front of the Boston and Providence Railroad Station (now gone).

This statue would benefit from some reinterpretation. In 1974, the Washington version was joined by a statue of civil rights leader and educator Mary McLeod Bethune who served as an adviser to Franklin Roosevelt. At that time, the Emancipation statue was rotated to face the statue of Bethune. Expanding the context of an anachronistic statue like this is important.

So what might be done in Boston? Perhaps additional panels explaining the context, Douglass’s criticism, and the efforts of Boston’s African-American civil rights leaders? Boston had an active African-American abolitionist community prior to the Civil War. Their stories are told through the National Park Service’s Black Heritage Trail and Museum of African American History but outside of that, there are few memorials in Boston to African-Americans who fought for emancipation. A statue of William Cooper Nell or Lewis and Harriet Hayden placed nearby would tell a different story to offset a well-intentioned but misguided Emancipation Monument.

[Update, July 2020: The Boston Art Commission voted on June 30, 2020 to remove this statue from Park Plaza and either place it in a museum or storage. I think that is the right call. Above, I suggested reinterpretation, however things have certainly changed and the need to reconsider and make changes to who and what we as society place on a pedestal is more urgent than ever. I still hope to see members of Boston’s active black abolitionist community honored in some form in the city’s public spaces. You can read more about the decision in this WBUR piece.]

[1] For an examination of the myth-making regarding Lincoln and emancipation see James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (2012), 329-335

[2] Renee Ater, Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller (2011), 86

[3] The Sanitary Commission oversaw soldiers’ relief efforts and constructed hospitals across the North during the war. As James Percoco writes in Summers with Lincoln: Looking for the Man in the Monuments (2009), 7, the Sanitary Commission, by the end of the war, had shifted much of their attention to relief for freedmen, particularly orphans. Percoco’s chapter on the monument is contains great historical detail and is worth a look for those who want to know more.

[4] Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (2007), 119

[5] Percoco, 14.

[6] Savage, 98.

[7] Frederick Douglass and John Lobb, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: from 1817-1882, (1882), 371

[8] Freeman Henry Morris Murray and John Wesley Cromwell, Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture: A Study in Interpretation, (1916), 119.